New life of old gasworks

Fot.

Fot.

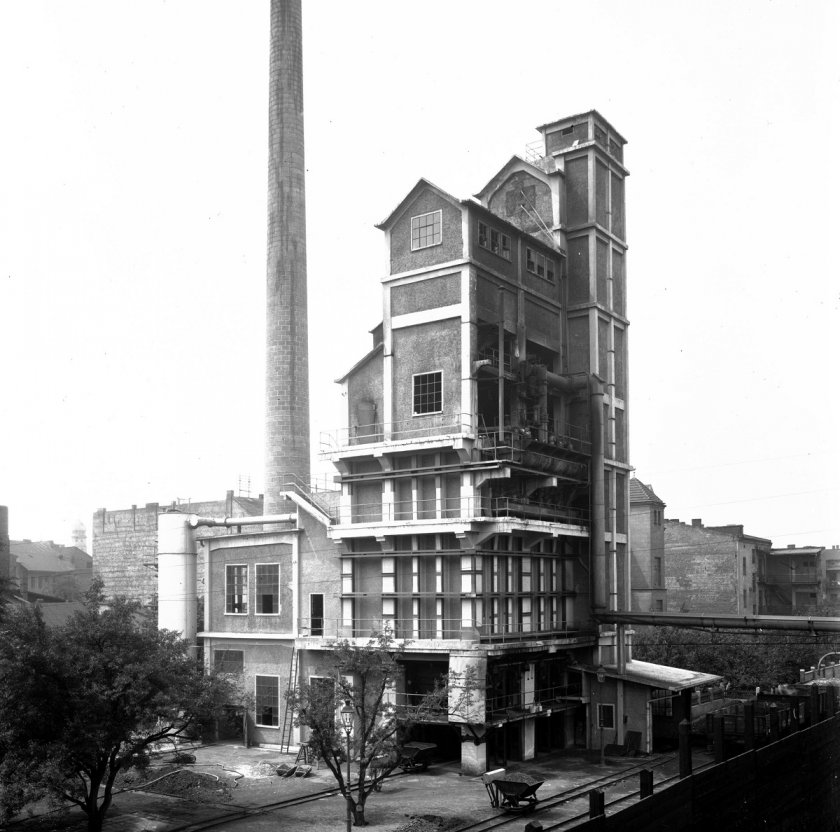

Let us imagine the industrial landscape of a larger city at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. Suburbs brimming with small workshops and larger plants. Among them, somewhere on the outskirts, a municipal gas plant was to be found, and its premises housed its inseparable element – a gas holder visible from afar. The holder was required for the technological process which created pressure and the illuminating gas pumped into the municipal gas network. The generated gas reached the gas lamps lighting the streets, houses and industrial plants, bringing with it light and energy that improved living conditions and fuelled economic development.

Over time, gasworks using hard coal were made superfluous as a result of the technological progress, the introduction of electrical energy, natural gas and urban development. Their often unpleasant demise resulted in their disappearance from urban landscapes. Only a few plants transformed into museums have survived in Poland. An example is the Gasworks Museum in Paczków which showcases the complete process line generating gas from coal. Sometimes, however, gasworks buildings were given a new lease of life and were adapted to perform new functions.

Hundreds of decommissioned gasworks left behind various reminders of their past, i.e. gas holders made of steel and concrete, and sometimes brick – of different sizes and based on diverse operating principles. In some circumstances, the inability to adapt them is due to a lack of a good idea or the lack of financial resources, with their impressive size remaining a substantial problem.

Hundreds of decommissioned gasworks left behind various reminders of their past, i.e. gas holders made of steel and concrete, and sometimes brick – of different sizes and based on diverse operating principles. In some circumstances, the inability to adapt them is due to a lack of a good idea or the lack of financial resources, with their impressive size remaining a substantial problem.

As the cities expanded, the value of the land on which these gas holders were situated was continuously growing. In consequence, many of them were cut down, dismantled, or demolished, and only old engravings or photographs are evidence of their existence. In many cases, their survival is limited to people’s memories. However, there are also some exceptions where human creative invention, considerable funds and imagination gave these objects a new life, most often completely unrelated to the gas industry.

In the south of the Greater Poland Province, in Ostrów Wielkopolski, a wet storage tank from the second half of the 19th century has been given a new use. On the completion of the gas holder’s conversion and adaptation, its interior houses the offices of an energy company and a bank. This unique project gave Ostrów an architecturally interesting building, with the shell of the gas holder being preserved for future generations. The structure can be seen at the intersection of Partyzancka and Zamenhofa Street.

In the south of the Greater Poland Province, in Ostrów Wielkopolski, a wet storage tank from the second half of the 19th century has been given a new use. On the completion of the gas holder’s conversion and adaptation, its interior houses the offices of an energy company and a bank. This unique project gave Ostrów an architecturally interesting building, with the shell of the gas holder being preserved for future generations. The structure can be seen at the intersection of Partyzancka and Zamenhofa Street.

Planetarium in Toruń, DerHexer/CC-BY-SA-3.0

Another innovative adaptation of a gas storage tank is the planetarium located in Toruń. The brick building was in use from 1860 as part of the municipal gas network. In 1989, work began on its adaptation to its new function. The authorities of the city of Toruń decided to house a planetarium inside it. One of the major changes was to cover the tank with a special projection dome.

The planetarium projection hall is where, thanks to specialised devices, popular astronomical presentations are shown to the public. These educational shows describe the size and structure of the Universe, illustrate the most well-known constellations in the sky, and uncover the secrets of planets and galaxies. This preserved gas tank, into which new life has been breathed, is visited annually by about 250 thousand people, which makes Toruń Planetarium one of the most popular facilities of its type in Europe. The first thing visitors see is the characteristic red brick rotunda. You can read more about this planetarium by looking at our Gas Map of Poland.

The planetarium projection hall is where, thanks to specialised devices, popular astronomical presentations are shown to the public. These educational shows describe the size and structure of the Universe, illustrate the most well-known constellations in the sky, and uncover the secrets of planets and galaxies. This preserved gas tank, into which new life has been breathed, is visited annually by about 250 thousand people, which makes Toruń Planetarium one of the most popular facilities of its type in Europe. The first thing visitors see is the characteristic red brick rotunda. You can read more about this planetarium by looking at our Gas Map of Poland.

While the gas holder in Ostrów and the one in Toruń are not of dizzying proportions, outside Poland’s borders there are a number of enormous gas storage holders for which new applications have been found. By way of an example, we can mention a 50,000 m³ gas holder in Ostrava in the Czech Republic, which has been adapted to house restaurants, training facilities for students, external companies, and a concert hall for almost 1,600 people. The entire facility has been equipped with modern audio-visual technological solutions, which have made it fit for the 21st century and transformed it into an important tourist destination on the post-industrial heritage map of Europe and the world as a whole.

Traveling further south, in Vienna we can make our way to see four giant brick gas tanks, each with a capacity of 90,000 m³, whose use has also changed dramatically. Instead of gas, they currently contain 800 apartments, a dormitory, a concert hall, a cinema and the municipal archives.

Traveling further south, in Vienna we can make our way to see four giant brick gas tanks, each with a capacity of 90,000 m³, whose use has also changed dramatically. Instead of gas, they currently contain 800 apartments, a dormitory, a concert hall, a cinema and the municipal archives.

These four gas tanks, called Gasometers, date back to the end of the 19th century and they still performed their main function, i.e. the storage of gas, in the early 1980s. They have been preserved by taking advantage of their industrial character and developing their interior space in line with the needs of this modern city.

However, old gas storage tanks are not the only facilities being adapted. Other elements of former gasworks are equally attractive. Here we can mention the ever-so-popular lofts, i.e. flats created in the adapted space of former industrial buildings. Such was the fate of the buildings comprising Hamburg Gasworks.

Sometimes, conversions are even more unusual – apart from conference facilities, restaurants or apartments, the old walls of former gasworks may also house wine bars. The human ingenuity and the desire to preserve industrial monuments bring those old, often forgotten and damaged structures back to life.

However, old gas storage tanks are not the only facilities being adapted. Other elements of former gasworks are equally attractive. Here we can mention the ever-so-popular lofts, i.e. flats created in the adapted space of former industrial buildings. Such was the fate of the buildings comprising Hamburg Gasworks.

Sometimes, conversions are even more unusual – apart from conference facilities, restaurants or apartments, the old walls of former gasworks may also house wine bars. The human ingenuity and the desire to preserve industrial monuments bring those old, often forgotten and damaged structures back to life.