Ignacy Mościcki

Fot.

Fot.

Mościcki was born in 1867, in the town of Mierzanów near Ciechanów, and grew up with five siblings. His education began at a middle school in Płock. Mościcki then left for Riga to seek higher education in chemistry at Riga Technical University, which was a popular alma mater amongst Polish students at that time.

However, his upbringing must have had a significant impact on the young Mościcki, who soon began to be consumed more by his patriotic spirit than the chemistry classes at the RTU. He found a vent for his need to act to the benefit of Poland’s raison d'être in local students’ associations and the Polish League.

Mościcki also founded the “Educational Club” – an underground academy for Polish students and soldiers. However, he most likely felt incomplete and sought a real challenge; ultimately, he made contact with the Social Revolutionary Party “Proletariat”, otherwise known as the Small Proletariat. Mościcki began helping the leftist revolutionaries in the publishing of underground papers and the circulation of political pamphlets.

Mościcki also founded the “Educational Club” – an underground academy for Polish students and soldiers. However, he most likely felt incomplete and sought a real challenge; ultimately, he made contact with the Social Revolutionary Party “Proletariat”, otherwise known as the Small Proletariat. Mościcki began helping the leftist revolutionaries in the publishing of underground papers and the circulation of political pamphlets.

The year 1892 was pivotal in Mościcki’s life: he married Michalina Czyżewska, and the first months of the marriage were rather dramatic. First, the newly-weds moved to Warsaw. Here, Mościcki finally aspired to do something that mattered. With his friend, Michał Zieliński, an anarchist of the Small Proletariat, he began plotting a suicide bomb attack on tsarist dignitaries.

This seemingly reckless enterprise helped Mościcki demonstrate his talents in chemistry. Mościcki set up a laboratory, where he successfully synthesised nitroglycerin. Russian security officials soon learned of what the would-be suicide bombers had planned. Before their first wedding anniversary, Mościcki and his wife decided to flee the Tsar’s enforcers to London.

This seemingly reckless enterprise helped Mościcki demonstrate his talents in chemistry. Mościcki set up a laboratory, where he successfully synthesised nitroglycerin. Russian security officials soon learned of what the would-be suicide bombers had planned. Before their first wedding anniversary, Mościcki and his wife decided to flee the Tsar’s enforcers to London.

During his immigrant years in England, the future President of Poland had to earn the family’s daily bread as a carpentry worker and a barber’s assistant. This did not stop him from experimenting with the production of kefir, a dairy product then still unknown in the British Isles. Unfortunately, there was only a handful of kefir connoisseurs among the culinary-conservative Londoners.

While Mościcki still needed to provide for his family, he kept on looking for opportunities to act for the liberation of Poland and social justice. It was in London where Mościcki befriended his peer in age and the then chairman of the Polish Socialist Party, Józef Piłsudski.

While Mościcki still needed to provide for his family, he kept on looking for opportunities to act for the liberation of Poland and social justice. It was in London where Mościcki befriended his peer in age and the then chairman of the Polish Socialist Party, Józef Piłsudski.

During his London years, Mościcki continued his education and took evening classes in chemistry. His innate talents soon let him grasp another opportunity: through the liaison with the local immigrants from Poland, he was hired as an assistant to Professor Wierusz-Kowalski at the University of Fribourg in Switzerland. There, he initially assisted in lectures given by the Professor; however, soon, under the guidance of his tutor, Mościcki started working on his own ideas.

These turned out to be incredibly practical. Some of Mościcki’s inventions from that time in his life continue to be used by us to this day. One of his discoveries established that two hermetically sealed panes of glass would not fog. Today, this invention is a common feature of modern windows.

These turned out to be incredibly practical. Some of Mościcki’s inventions from that time in his life continue to be used by us to this day. One of his discoveries established that two hermetically sealed panes of glass would not fog. Today, this invention is a common feature of modern windows.

Ignacy Mościcki in a laboratory

NDA/public domain

The subsequent career of Mościcki in engineering was defined by a more strategic problem. The economies of the world began lacking a critical industrial material – saltpetre. Chemists knew that saltpetre is compounds of nitrogen and started looking to where nitrogen is in abundance – the atmosphere. The research focused on the already known method of nitrogen oxidation in electric arcs. While the method was feasible in laboratory conditions, no one knew how to apply it on an industrial scale.

Mościcki began researching the problem in 1901. He understood that the obstacle for the industrial application of the electric-arc oxidation of nitrogen was the feasibility of generating electricity at extremely high voltages. There were still no electrical capacitors to enable it. Mościcki picked up the gauntlet and soon the Patent Office in Brno received his application for the design of a contraption which resembled a tube made of thick glass.

Mościcki began researching the problem in 1901. He understood that the obstacle for the industrial application of the electric-arc oxidation of nitrogen was the feasibility of generating electricity at extremely high voltages. There were still no electrical capacitors to enable it. Mościcki picked up the gauntlet and soon the Patent Office in Brno received his application for the design of a contraption which resembled a tube made of thick glass.

It was Mościcki’s high-voltage capacitor, an invention which became indispensable in the chemical industry. Their applications were expanded to include industrial power grids and installations built in locations as unusual as the needle of the Eiffel tower, where they supplied current to a very powerful radio station.

The invention of Mościcki attracted the interest of Aluminium Industrie A.G. In 1910, Mościcki commissioned a nitrogen acid synthesis plant for this German corporation, sold his patent rights for a considerable sum and became a man of affluence. When he achieved what seemed to be the pinnacle of his career in scientific research and innovation, an opportunity to serve Poland became apparent.

The invention of Mościcki attracted the interest of Aluminium Industrie A.G. In 1910, Mościcki commissioned a nitrogen acid synthesis plant for this German corporation, sold his patent rights for a considerable sum and became a man of affluence. When he achieved what seemed to be the pinnacle of his career in scientific research and innovation, an opportunity to serve Poland became apparent.

In 1912, Mościcki was invited to take the chair of technical electrochemistry and physical chemistry at the Polytechnical School in Lviv, from where he was promoted to the dean of the Faculty of Chemistry. This was a perfect place and a perfect time for Mościcki – right at the doorstep of Poland’s reconstitution and at the heart of the booming oil and gas mining industry.

During his Lviv years, Mościcki was a scientist and a proactive facilitator of the Polish industry. Mościcki began collaborating with inventors and businessmen who later rebuilt the liberated Poland as the Second Republic. This society decided to attract promising engineers to Lviv by jointly establishing the “Metan” Research Institute, an organisation founded to create and sell patent rights while providing business support for entrepreneurs.

During his Lviv years, Mościcki was a scientist and a proactive facilitator of the Polish industry. Mościcki began collaborating with inventors and businessmen who later rebuilt the liberated Poland as the Second Republic. This society decided to attract promising engineers to Lviv by jointly establishing the “Metan” Research Institute, an organisation founded to create and sell patent rights while providing business support for entrepreneurs.

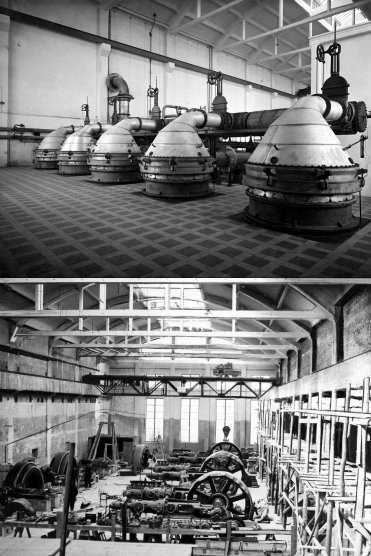

Państwowa Fabryka Związków

Azotowych w Mościcach

NDA/public domain

The ranks of the enterprising men were joined by Władysław Szaynok and Marian Wieleżyński, Polish industrialists and pioneers of industrial applications of natural gas. Szaynok, Wieleżyński and Mościcki founded a joint-stock company “Gazolina” with a mission of mining, processing and the resale of kerosene and natural gas.

Poland regaining its independence coincided with Mościcki developing solutions to support the Polish oil and gas industry. His inventions were used in all major oil and gas mines and processing plants, including the Factory of Mineral Oils in Drohobych, the refinery in Glinik Mariampolski near Gorlice, and the refinery in Jedlicze.

Poland regaining its independence coincided with Mościcki developing solutions to support the Polish oil and gas industry. His inventions were used in all major oil and gas mines and processing plants, including the Factory of Mineral Oils in Drohobych, the refinery in Glinik Mariampolski near Gorlice, and the refinery in Jedlicze.

The crowning of Mościcki’s work in Lviv came in 1925, with his election for the office of the Rector of the Lviv Polytechnic. Mościcki declined the position in favour of the chair at the Department of Technical Electrochemistry at the Warsaw University of Technology. Yet his protracted stay in Warsaw had nothing to do with his beloved research and inventions; Mościcki responded to the call of politics.

In 1926, the May Coup was successfully attempted, and Józef Piłsudski, a friend from the underground socialist years, asked Mościcki to become the President of Poland. Mościcki accepted the presidency from the National Assembly in June of that year. He was sworn as the President and remained a loyal partner to Piłsudski, although at the cost of more than one difficult decision.

In 1926, the May Coup was successfully attempted, and Józef Piłsudski, a friend from the underground socialist years, asked Mościcki to become the President of Poland. Mościcki accepted the presidency from the National Assembly in June of that year. He was sworn as the President and remained a loyal partner to Piłsudski, although at the cost of more than one difficult decision.

Ignacy Mościcki

NDA/public domain

Mościcki did not abandon his aspirations as an engineer, and the industry remained his life’s passion. As a fulfilment of his life-long dream, he released his patents for the synthesis of nitrogen to the Polish state. In 1927, the construction of the State Works of Nitrogen Compounds began in Mościce near Tarnów.

Mościcki also supported Eugeniusz Kwiatkowski, his former colleague from Lviv and the Vice-Prime Minister during Mościcki’s presidential term in the development of the Central Industrial Region.

Mościcki also supported Eugeniusz Kwiatkowski, his former colleague from Lviv and the Vice-Prime Minister during Mościcki’s presidential term in the development of the Central Industrial Region.

In 1933, Mościcki was re-elected the President of Poland. Unfortunately, he had very little time to foster the growth of his most significant undertakings, designed to industrialise Poland after decades of stagnation.

When the USSR invaded Poland in 1939, Mościcki fled to Romania. He renounced his presidency and returned to Switzerland and his career in engineering. From then on, Mościcki worked at a chemical laboratory, incessantly developing more inventions. He continued in his work until his health deteriorated in 1943. Mościcki died three years later in Versoix near Geneva.

When the USSR invaded Poland in 1939, Mościcki fled to Romania. He renounced his presidency and returned to Switzerland and his career in engineering. From then on, Mościcki worked at a chemical laboratory, incessantly developing more inventions. He continued in his work until his health deteriorated in 1943. Mościcki died three years later in Versoix near Geneva.