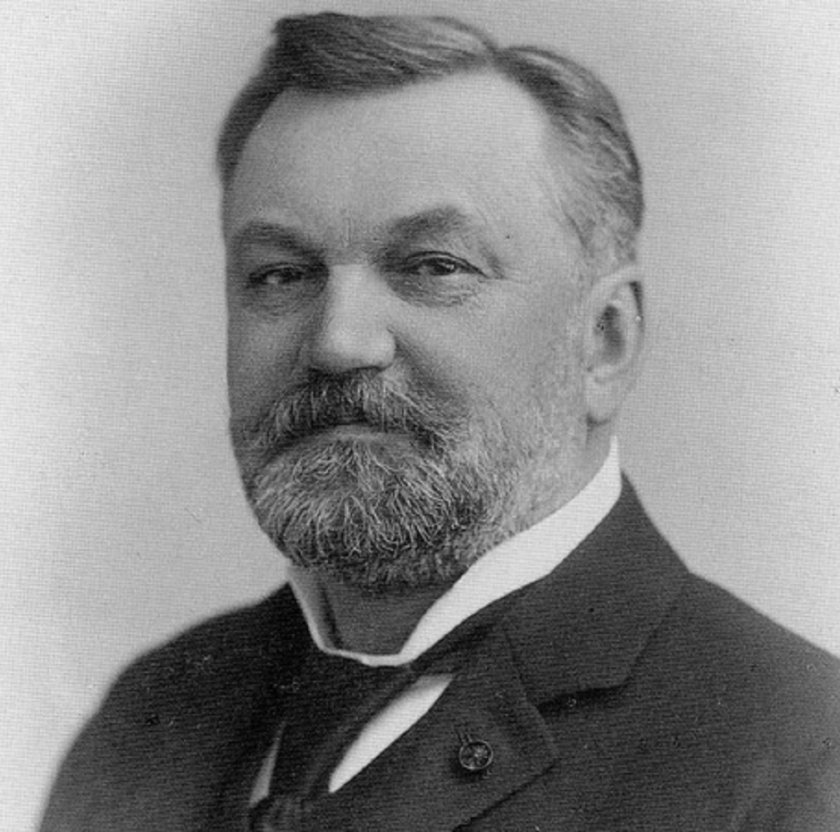

William Murdoch

Fot.

Fot.

The family tradition was continued by William’s father, who worked as a miller and continued to improve his plant. His machines were appreciated by other millers, so they eagerly made use of his ideas. The young William had plenty of time to learn everything it takes to become an inventor from his father. He worked in his father’s plant until the age of 23. Together, they created improvements to many mills.

At that time, the steam revolution was gaining momentum. In the distant English town of Birmingham, whistles of the first steam engines were heard. They were produced at the Soho Manufactory, owned by Boulton & Watt.

The plant was founded by industrialist and investor Matthew Boulton and the owner of the steam machine patent, James Watt. William Murdoch arrived in Birmingham in 1777 and decided to find employment in this modern company. The son of a miller from Scotland immediately drew the attention of his business partners with his talent and the love of machines brought from his family home. He was given a very responsible task in the company – to start up the steam engines installed in the mines in Cornwall, the largest mining hub in England.

The plant was founded by industrialist and investor Matthew Boulton and the owner of the steam machine patent, James Watt. William Murdoch arrived in Birmingham in 1777 and decided to find employment in this modern company. The son of a miller from Scotland immediately drew the attention of his business partners with his talent and the love of machines brought from his family home. He was given a very responsible task in the company – to start up the steam engines installed in the mines in Cornwall, the largest mining hub in England.

Soon, the young Scotsman became the closest associate of the company owners. Along with them, he received visitors to the plant. Steam engines aroused great interest, and the company was visited by people of science and politics, ambassadors and the royalty. Prince Józef Poniatowski, among other well-known names, was one of those visitors.

However, work on the implementation of other people’s designs was not enough for the descendant of the inventors’ family to fulfil his vocation. He wanted to further develop the unlimited, as they seemed then, possibilities of the steam engine, dreaming of constructing a steam-powered vehicle.

However, work on the implementation of other people’s designs was not enough for the descendant of the inventors’ family to fulfil his vocation. He wanted to further develop the unlimited, as they seemed then, possibilities of the steam engine, dreaming of constructing a steam-powered vehicle.

Unfortunately, the realisation of this dream was to bring tragic consequences. William continued to work in the mines in Cornwall and lived in the town of Redruth. In his spare time, he was busy constructing a small tri-wheeled vehicle. The model was equipped with a heated water tank. It had a cylinder with a piston connected to the crankshaft, which drove the wheels.

Soon, the project was ready. One night, on his return from the mine, William started up his vehicle. As the location for his experiment, he chose the road near the church in Redruth. When the water was heated, the steam actuated the piston in the cylinder, and the vehicle started to move. After a while, it accelerated so much that the inventor was unable to get hold of it! The noise woke the vicar. The elderly clergyman was terrified – in the smoking machine that flashed fire he saw a manifestation of infernal forces.

Soon, the project was ready. One night, on his return from the mine, William started up his vehicle. As the location for his experiment, he chose the road near the church in Redruth. When the water was heated, the steam actuated the piston in the cylinder, and the vehicle started to move. After a while, it accelerated so much that the inventor was unable to get hold of it! The noise woke the vicar. The elderly clergyman was terrified – in the smoking machine that flashed fire he saw a manifestation of infernal forces.

The Anglican vicar from Redruth was probably the first victim of motorisation – he became so terrified that he died of a heart attack.

After the incident, and also because similar constructions may have violated James Watt’s patent rights, the employers dissuaded Murdoch from further work on steam vehicles. They claimed that engines that ran on wheels themselves were pure fantasy and a waste of time …

After these events, it seemed that William would abandon his dreams of a great invention. In 1785, he got married and bought a house. However, the spirit of the inventor inherited from his ancestors manifested itself once again. The inhabitants of Redruth would soon see a strong white light coming from the windows of Murdoch’s house on Cross Street.

After the incident, and also because similar constructions may have violated James Watt’s patent rights, the employers dissuaded Murdoch from further work on steam vehicles. They claimed that engines that ran on wheels themselves were pure fantasy and a waste of time …

After these events, it seemed that William would abandon his dreams of a great invention. In 1785, he got married and bought a house. However, the spirit of the inventor inherited from his ancestors manifested itself once again. The inhabitants of Redruth would soon see a strong white light coming from the windows of Murdoch’s house on Cross Street.

Murdoch experimented with coal pyrolysis, i.e. he did in his workshop what his wife could have done in the kitchen at the time. He discovered that, just as by heating sugar one can turn it into liquid caramel, so with a high temperature you can change the properties of coal. By heating coal in the absence of air, most pollutants can be eliminated from hard coal, thus even more efficient fuel can be obtained.

However, Murdoch was primarily interested in whether it was possible to make use of what escaped from coal during heating. He managed to construct a prototype retort – a device that would soon be widely used in many cities. At first, it resembled a boiler with a twist-off lid.

However, Murdoch was primarily interested in whether it was possible to make use of what escaped from coal during heating. He managed to construct a prototype retort – a device that would soon be widely used in many cities. At first, it resembled a boiler with a twist-off lid.

To this “homemade retort” Murdoch connected an entire pipe system, leading to both the kitchen and the workshop. At the end of the pipes, he installed special burners in which the gas released in the retort from coal was burned. In this way, his house was filled with light, which must have surprised the townsfolk with its unusual colour and brightness.

In 1792, the house on Cross Street in Redruth became the first building lit by gas. The halls of the Soho Manufactory, where Murdoch continued to work, were soon to follow. Shortly afterwards, gas lamps appeared on the streets of major European cities. This is how a son of a Scottish miller drove the darkness out of cities.

In 1792, the house on Cross Street in Redruth became the first building lit by gas. The halls of the Soho Manufactory, where Murdoch continued to work, were soon to follow. Shortly afterwards, gas lamps appeared on the streets of major European cities. This is how a son of a Scottish miller drove the darkness out of cities.