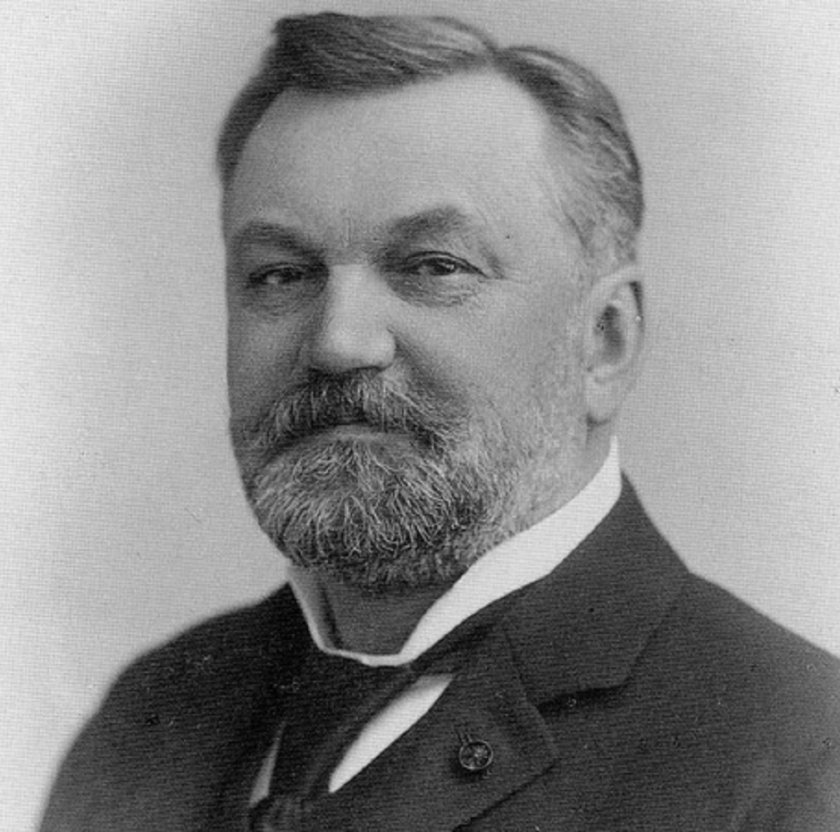

Stanisław Szczepanowski

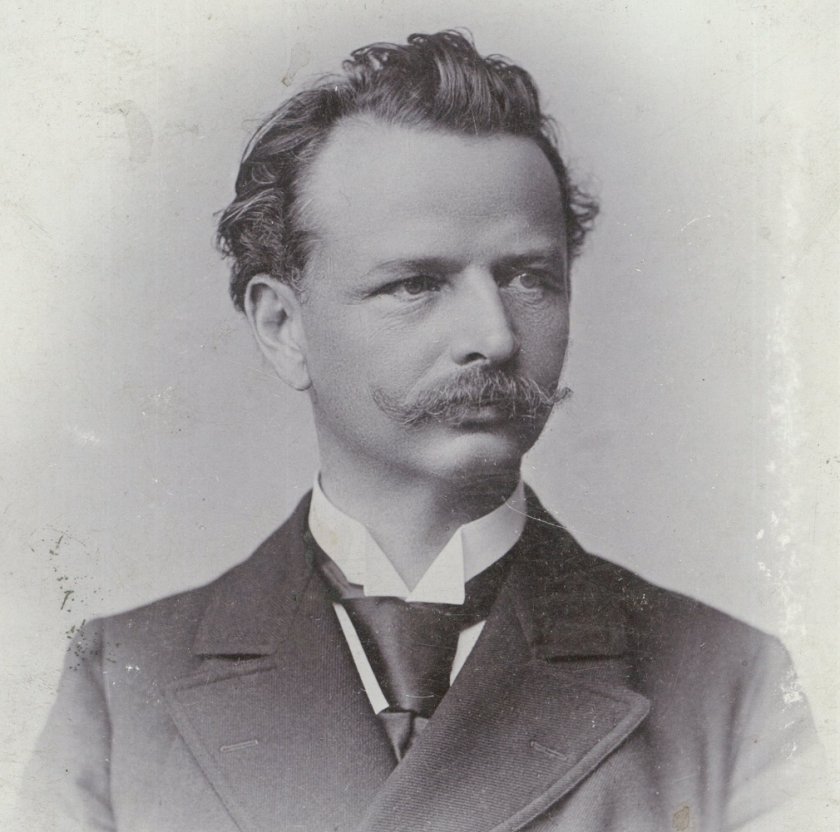

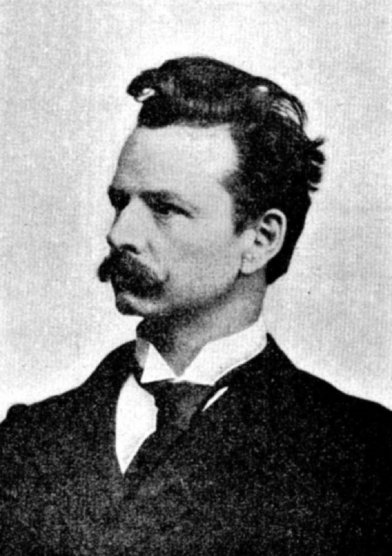

Fot.

Fot.

Stanisław Szczepanowski took up studies at the Vienna University of Technology and continued his education at École Centrale des Arts et Manufactures in Paris. The diligent student graduated with a degree in engineering in London, where he studied chemical technologies and economics between 1869 and 1871. Throughout his entire university studies, Szczepanowski shared his passion for education with a passion for sports, especially gymnastics, horse riding and mountain trekking.

Having graduated in London, he decided to remain in England, where the textile industry only began to develop to drive the global industrial revolution. Szczepanowski witnessed how innovation turned pre-industrial manufacturing into mechanised factories, while the economy entered a stage of globalisation that had never been seen before. He began to actively contribute to this process. During his career at the India Office of the British Cabinet, Szczepanowski drafted investment plans for the building of railroads and cotton field irrigation systems in India. The plans worked perfectly, although their creator never set foot on the Indian subcontinent.

When Szczepanowski’s career reached its peak in Britain, he was finally invited to visit India by Albert Edward of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, the then successor to Queen Victoria who later became King Edward VII.

When Szczepanowski’s career reached its peak in Britain, he was finally invited to visit India by Albert Edward of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, the then successor to Queen Victoria who later became King Edward VII.

Szczepanowski then made a surprising decision – he declined Edward’s invitation and instead left for Galicia in 1879, travelling to the land where his father once used to build railroads.

In those days, Galicia was a part of Poland occupied by the Austro-Hungarian Empire of the Habsburg dynasty. It was also one of the first European locations where oil mining facilities were established. Driven by “oil fever”, businessmen arriving in Galicia were later proven to be right to believe that oil would be the lifeblood of the global economy.

Szczepanowski also joined in the search for the black gold. His intuitive decision to start drilling for oil in the village of Słoboda Rungurska north of Lviv was well rewarded.

In those days, Galicia was a part of Poland occupied by the Austro-Hungarian Empire of the Habsburg dynasty. It was also one of the first European locations where oil mining facilities were established. Driven by “oil fever”, businessmen arriving in Galicia were later proven to be right to believe that oil would be the lifeblood of the global economy.

Szczepanowski also joined in the search for the black gold. His intuitive decision to start drilling for oil in the village of Słoboda Rungurska north of Lviv was well rewarded.

Soon, the name of this small village became the buzzword of the oil industry around the globe. The oil mine established by Szczepanowski had the highest yield in the whole of Galicia, with more than half of the total output in the area.

Szczepanowski did not become complacent after his first success. He opened a factory of mining equipment and a state-of-the-art oil refinery in Pechenizhyn. Szczepanowski engineered and constructed an oil pipeline which fed the output of the mine in Słoboda Rungurska to the Pechenizhyn refinery, as well as a railroad. In 1888, he continued drilling for oil in the nearby town of Schodnica until he found more high-yield oil fields. Szczepanowski managed to drill deeper than anyone else and his oil wells could output up to ten-odd rail wagons of oil each day.

Szczepanowski did not become complacent after his first success. He opened a factory of mining equipment and a state-of-the-art oil refinery in Pechenizhyn. Szczepanowski engineered and constructed an oil pipeline which fed the output of the mine in Słoboda Rungurska to the Pechenizhyn refinery, as well as a railroad. In 1888, he continued drilling for oil in the nearby town of Schodnica until he found more high-yield oil fields. Szczepanowski managed to drill deeper than anyone else and his oil wells could output up to ten-odd rail wagons of oil each day.

The importance of Szczepanowski’s discoveries and operations was described by Władysław Długosz, another renowned oil engineer from Galicia: “Before Szczepanowski found the oil fields in Słoboda Rungurska, the Galician output of oil was measured in mere gallons. After Słoboda, we started drawing oil in barrels, but when Szczepanowski surveyed oil in Schodnica, the output grew to rail wagons.”

The successes of his big business did not hamper success in the private life of Szczepanowski, who proposed to Helena Wolska, the daughter of a notary from Lviv. The Szczepanowski family grew quickly to two sons and three daughters.

The successes of his big business did not hamper success in the private life of Szczepanowski, who proposed to Helena Wolska, the daughter of a notary from Lviv. The Szczepanowski family grew quickly to two sons and three daughters.

Stanisław Szczepanowski

Wikimedia Commons/public domain

Business and engineering were not the only areas in which Szczepanowski devised his ambitious undertakings. Szczepanowski also strived to look after his employees, which was something uncommon among the businessmen in Galicia during the oil revolution. The engineer commissioned the construction of housing projects for his workers, supporting retail cooperatives and local community centres. He also founded a savings and insurance union for the workers. These accomplishments place Szczepanowski in the hall of fame of the social responsibility innovators of the era.

Already as a well-known oil mogul, Szczepanowski turned to politics. He cared for his business and more, the livelihood of the people in Eastern Galicia. The oil mining industrialised the region, but there was still much to be done to bring it out of poverty and stagnation.

Already as a well-known oil mogul, Szczepanowski turned to politics. He cared for his business and more, the livelihood of the people in Eastern Galicia. The oil mining industrialised the region, but there was still much to be done to bring it out of poverty and stagnation.

Szczepanowski voiced his conviction that the standards of living could be improved by the continued growth of the oil industry. However, the sector faltered under the Austrian taxes on oil mining and high rail freight charges for petrochemical products. Szczepanowski advocated that for the oil industry to grow unhampered, it must be exempted of taxes for ten years, just like in the United States.

These efforts won him voters and enemies alike. Szczepanowski was elected as a member of the parliament in Vienna and held the office between 1886 and 1897. While an MP, he managed to reduce the rail freight charges for oil. Szczepanowski also formulated a program for social reforms discussed in the book entitled “Poverty of Galicia in Figures and a Program for the Energetic Development of the Economy of the Country”.

These efforts won him voters and enemies alike. Szczepanowski was elected as a member of the parliament in Vienna and held the office between 1886 and 1897. While an MP, he managed to reduce the rail freight charges for oil. Szczepanowski also formulated a program for social reforms discussed in the book entitled “Poverty of Galicia in Figures and a Program for the Energetic Development of the Economy of the Country”.

The book was a vessel for Szczepanowski’s criticism of the Austro-Hungarian imperial statecraft which he accused of treating Galicia like a remote colony exploited for resources and recruits for the army. Szczepanowski went even further: not only did he demand increased budget expenditure for the development of Galicia, he also wanted systemic reforms through the decentralisation of power and increased local autonomy from the government in Vienna.

This was highly unwelcome among the Austrian officials and the conservative nobility of Galicia which profited from the “colonial” system in their region. Trouble started brewing for Szczepanowski; his successes aside, he didn’t quite manage to control his legal and financial matters. Investment after investment, Szczepanowski’s debt grew in a dynamic environment of the Galician oil fever, where the pricing of oil and oil well lots was highly fluid, rendering commercial operations increasingly unpredictable.

This was highly unwelcome among the Austrian officials and the conservative nobility of Galicia which profited from the “colonial” system in their region. Trouble started brewing for Szczepanowski; his successes aside, he didn’t quite manage to control his legal and financial matters. Investment after investment, Szczepanowski’s debt grew in a dynamic environment of the Galician oil fever, where the pricing of oil and oil well lots was highly fluid, rendering commercial operations increasingly unpredictable.

In 1894, Kasimir Felix Badeni, the Imperial-Royal stadtholder of Galicia, forced Szczepanowski to pay the debt by selling the oil well plot in Schodnica. It was purchased by the Anglobank of Vienna for one million guldens. One year later, the same oil well lot was worth fifteen times its selling price, while Szczepanowski sank deeper in debt.

Harassed by accusations of securing funding with illegal loans, Szczepanowski began to suffer from health problems. Although the court proceedings were found in his favour thanks to the testimonies of Henryk Sienkiewicz and Bolesław Prus, Szczepanowski’s career was crippled. He left for a health resort in Bad Neuhaim and died there in 1900, at the turn of the century of oil and engineering.

Harassed by accusations of securing funding with illegal loans, Szczepanowski began to suffer from health problems. Although the court proceedings were found in his favour thanks to the testimonies of Henryk Sienkiewicz and Bolesław Prus, Szczepanowski’s career was crippled. He left for a health resort in Bad Neuhaim and died there in 1900, at the turn of the century of oil and engineering.

In his “Poverty of Galicia in Figures (…)”, Szczepanowski listed typically engineering-like calculations with proposals for merging Polish patriotism and business:

“May all those men ready to die for the country die not, but live and work instead; for as our great poet said, their life will be a hundred times more useful than even the most heroic sacrifice of life. Their efforts focused on a noble purpose will immediately make the men believe that their work is effective and have them build a conviction that one day they will pull themselves out of the dark clouds of today. With their spirits changed for the better, they will cast aside the narrow conventions and trivial fears which now bind your public life and do not allow the measures which have been long tried and proven by other nations”.

(S. Szczepanowski, Poverty of Galicia in Figures and a Program for the Energetic Development of the Economy of the Country, Lviv 1888).

“May all those men ready to die for the country die not, but live and work instead; for as our great poet said, their life will be a hundred times more useful than even the most heroic sacrifice of life. Their efforts focused on a noble purpose will immediately make the men believe that their work is effective and have them build a conviction that one day they will pull themselves out of the dark clouds of today. With their spirits changed for the better, they will cast aside the narrow conventions and trivial fears which now bind your public life and do not allow the measures which have been long tried and proven by other nations”.

(S. Szczepanowski, Poverty of Galicia in Figures and a Program for the Energetic Development of the Economy of the Country, Lviv 1888).