Gas light enters cities

At a time when city streets were bathed in darkness and candles were used to light building interiors, city dwellers approached the new gas lighting technology with great caution. They had good reason for it! First of all, the gas generated from coal was expensive. Its production required investments in municipal gasworks and distribution networks. Secondly, the gas flame created an unpleasant smell and soot. Although street lighting was not affected, homes had to be regularly aired and painted. Thirdly, the light of the first gas lamps had a low luminous intensity.

How did it happen that, despite these difficulties, gas lighting became commonplace?

The new technology was developing gradually. The new type of fuel raised high hopes, which meant that the gas production process was being intensively enhanced, leading to the generation of increasingly cleaner gas. The coal residues it contained – smelly and smoky substances – were removed using a system of filters and scrubbers.

Time for a breakthrough

The popularisation of gas was made easier by an inconspicuous invention resembling a bag made of white mesh. In 1885, the Austrian chemist Karol Auer von Welsbach soaked the cotton fabric with non-flammable compounds of two elements: thorium and cerium. When placed over a gas burner, this mesh began to give off a beautiful white light. This particular invention explains the characteristic milky-white colour of the light produced by gas lamps. Now, it was easier to overcome another obstacle linked to gas light – the cost of gas use.

The bright gas light was unlike anything used previously to illuminate houses and streets. Its illuminance level was, therefore, measured by comparing it to the number of candles needed to achieve a similar effect. One gas lamp gave about as much light as twelve candles, and thanks to the Welsbach mantle it had a whiter colour, which was more similar to daylight. This encouraged the city residents to install gas lighting, which in turn led to the expansion of the gas network and the gradual reduction of costs.

Inconspicuous invention

Karl Auer von Welsbach worked at the University of Vienna, where he studied chemical elements. He discovered that some of them emit light when heated to high temperatures. Welsbach decided to put this phenomenon to use in his invention – he applied a mixture of thorium (99%) and cerium (1%) to cotton mesh in accurate proportions. When placed over a gas burner, this mesh began to give off a beautiful white light when heated. Because of its shape and the material used, this invention was also referred to as an incandescent gas mantle.

Light means changes

The new source of light introduced many changes to domestic and social life. Some appreciated longer evenings which they could spend on reading books or attending a beautifully illuminated opera house. Others found their working time mercilessly extended, as industrialists were able to operate their factories, illuminated with this new type of fuel, also at night-time.

Although the cost of gas gradually dropped, the workers’ families could only afford a tallow candle at most. This situation only changed after the introduction of gas meters which used coins or tokens.

Gas for tokens

The gas payment methods changed similarly to the ways in which gas was used. One of the most fascinating inventions were gas meters fitted with an automated slot mechanism. At the end of the 19th century, such devices were commonplace and practical – gas was supplied to the home only once a special token was inserted into the meter. Tokens could be purchased from the gasworks. Similarly to coins, they had different denominations and allowed to purchase different quantities of gas. This made it easier for customers to settle their bills – gas was delivered “on-demand” when it was needed, and the gasworks no longer had to deal with the problem of unpaid bills and having to prepare labour-intensive estimates of consumed gas based on gas meter readings taken by meter reading agents.

Ornamentation only for the wealthy

Gas lamps, chandeliers and pendants were mostly reserved for wealthy townsfolk. They were designed to satisfy the tastes which were not always the most sophisticated. Some gas lamps featured elaborate designs which did not shy away from gilded decorations and crystal pendants.

Exhibit gallery

Mementoes of history

Gas lighting became a thing of the past, just like many other technologies developed and abandoned by mankind. Some cities, however, have preserved their street gas lamps and continue to attract visitors who are curious about this method of lighting. The warm white light coming from the Welsbach mantle was once a symbol of progress while today it forms a part of the historical heritage.

The last gas lanterns are given the respect they deserve – in many cities they are maintained not only by municipal employees but also by gas light enthusiasts. This is the case in London, where as many as 1490 street gas lamps are still operational. They can be found, for example, in the district of Westminster – illuminating the National Gallery, the Westminster Cathedral and the building of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. The street lamps are lit and maintained by lamp attendants working for the British Gas company.

Gas lanterns also illuminate the most beautiful locations in Prague – the Charles Bridge and the Royal Route. Visitors to Prague often make their way to see the impressive gas lamp towering over the square outside the castle in Hradčany. Still, the real European capital of gas light is Berlin. There are currently more than 20,000 street gas lamp in Germany’s capital, although they are gradually being replaced by electric lighting.

The most interesting designs can be seen in the Tiergarten park. One of its alleys comprises approximately 90 lamp posts transferred from many European cities. These include: Dublin, Bruges, Zurich, Budapest and Copenhagen.

Street gas lamps in Poland

Wrocław is the Polish town which is mostly associated with gas light – there are 103 street gas lamps illuminating Ostrów Tumski, the city’s historical part. This is only a small reminder of the gas lighting system, which once consisted of over 12,000 street lamps.

Individual street gas lanterns can also be seen in numerous Polish cities. Some of them are still functional, while others have only been partially preserved. Hidden amongst the new urban landscape, they are a real treat for history enthusiasts and intrepid explorers thirsty for adventure.

Street gas lamps in Agrykola Park

Today, it is possible to feel the magic of the days gone by taking a stroll along Agrykola Street. On the occasion of its 150th anniversary, Warsaw Gasworks renovated the historic gas street lamps in Agrykola Street and the street is now exclusively lit by gas.

Gas lamps in Kraków’s Cloth Hall

The lamps installed in the 19th century can still be seen today inside the Cloth Hall in Kraków. Until recently (since the lamps are no longer lit) their gas light, the horse-drawn carriages and the bugle call coming from the Bugle-call Tower all created the magical atmosphere of the Kraków of old.

Gas street lamp in Niemodlin

The cast iron lamp erected in Niemodlin in 1909 weighed over 700 kg and was exquisitely decorated with acanthus leaves and figurines of dragons holding the lampshades. Although it is no longer powered by gas, every effort was made to obtain the characteristic colour of gas light.

See other virtual exhibitions

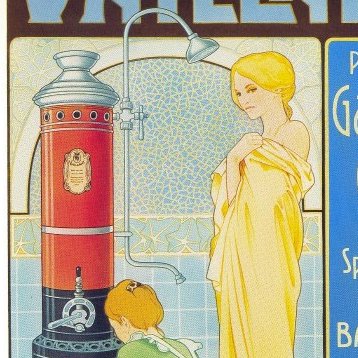

History of gas advertising and promotion

Gas equipment manufacturers were faced with a considerable problem – how to persuade people who were used to cooking on coal and lighting their homes with candles to use appliances powered by a new, previously unknown fuel?

Household gas-powered appliances

These silent companions of our daily lives are also evocative of global civilizational changes. Although today we associate stoves, heaters and refrigerators with electricity, in the 19th century they were powered by … gas. The introduction of these appliances to people’s homes heralded a lifestyle revolution that continues to this day.

The Earth’s fire at the beck and call of cities

An accidental visitor to a traditional gasworks will see a tangle of pipes, some baffling geometrically-shaped installations and mystifying devices. Such a gas plant resembles an octopus with a thousand tentacles, which has crawled out of the canal at the edge of the city. What happens inside this tangle of pipes? What are the mysterious towers for?